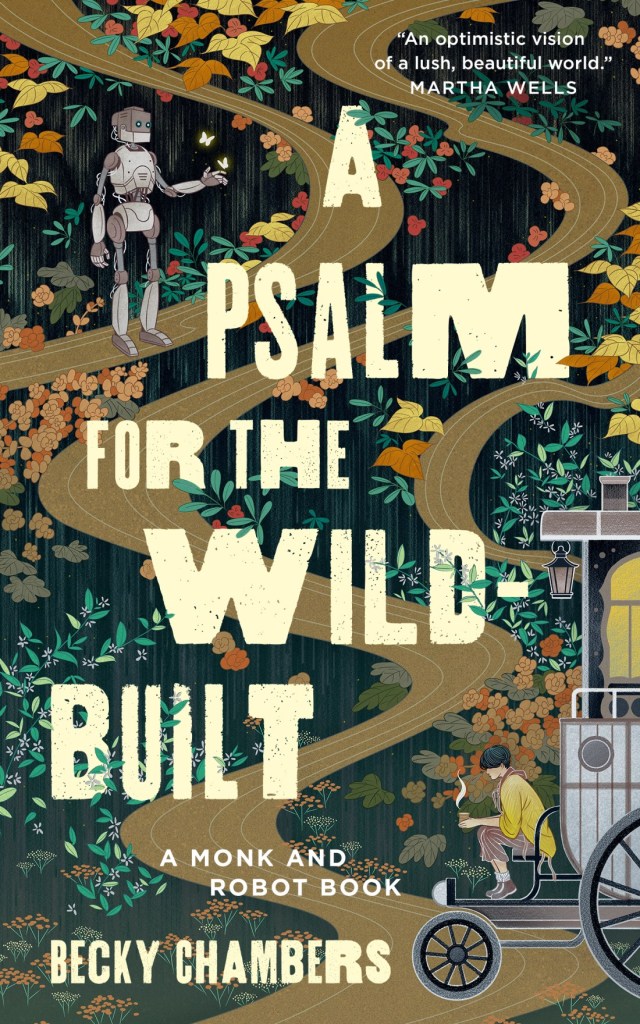

Book: A Psalm for the Wild-Built (#1) & A Prayer for Crown Shy (#2)

Author: Becky Chambers

Year: 2021 & 2022 (respectively)

Booked Rating: ❤️❤️❤️

When I read Becky Chambers’ Wayfarer outing A Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet a nagging thought never left me. Why, I wondered, did science fiction set thousands of years into the future have the exact social and political structures as we did today? How was it that even after thousands of years, when building wormholes has become a 9-5 day job, all kinds of species are still in conflict over a love affair between a Human and an AI? I didn’t continue reading the Wayfarer series, but overall, I did think she was able to keep a story going, the writing was fluid, even if the world building could do with depth. I came away from A Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet with a fairly open mind and did not critique it the way I did with the Monk and Robot series.

After reading the two books in the Monk and Robot series A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for Crown-Shy, the thought continues in a similar vein — how is it that even after humanity survives climate change (even though Planet Earth does not) we are still seeing the characters spout Instagram philosophy as conversation and the crickets don’t sing in the city, so much so that Sibling Dex, the main character, leaves their life behind to go in search of a cricket song? The world was supposed have healed, isn’t it? So why undertake a treacherous journey to go and listen to the crickets sing? For a story that tries to embody the solar punk movement while exploring an inner-struggle of dissatisfaction that humans sometimes experience, I found that Chambers left more to be desired in this conversational-philosophy series of novellas.

A really beautiful conversation-philosophy novel that comes to mind is Tuesdays with Morrie which does this better. If you want a movie, Good Will Hunting is superlative in its dialogue and banter. Or if I had to search the recesses of my mind for characters who were struggling internally while seeking a higher purpose, I think of the relationship between Lee and Adam in East of Eden where Lee, even as a secondary character, is more measured and profound about the complexity of human existence; and even simple conversations between him and Adam explore eloquently the conflicts that exist within the heart and in life. As Chambers puts it, she has written ‘A Psalm for the Wild-Built’ for anyone “who could use a break” because the main character needs a break from the routine due to an unexplained internal struggle and goes in search of crickets.

Sibling Dex is a tea monk on a moon called Panga who leaves their plush job in the monastery and gets on their ox-bike to go village-to-village and talk to people over a cup of tea. In the beginning, they’re unable to be a tea-monk adequately well because they’ve never done it before, but as time passes they get better at brewing different teas based on what ails the people who come to talk to them. There are few references on the kinds of teas being brewed, but there isn’t a single worthy conversation between Dex and someone who comes to them for their services. While on this journey, they decide to leave the city and go into the mountains in the Antlers to listen to the crickets sing because they’re weary of their job (as most of us are, which probably explains the book’s dedication). While on this treacherous journey, they meet Mosscap, a robot who is a wild-built, which means they’ve been made from the parts of other robots who gained consciousness and then parted from the humans to live on their own, in their own society, out in the wild.

The Hart’s Brow Hermitage was a remote monastery located near the summit of one of the lower mountains in the Antlers.

Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (p.37), Kindle Edition

Mosscap offers to accompany Dex on this pilgrimage in exchange for education on how humans live. A reluctant Dex hesitates because they don’t want to have a robot around who can help them, because that’s what traditionally robots were supposed to do for humans — serve & help — but they agree because they don’t know how to survive in the wild. There’s also a bear involved in this decision-making. What follows is a conversation between a monk and a robot. In this world of Panga, gods still exist and have their quirks, wilderness still has far and fewer animals, streams are untended, a robot doesn’t know what a paper book is, a monk is not as eloquent as the robot, so on and so forth. The lack of depth in Dex’s character really comes to the fore when Mosscap arrives as they’re braver, adventurous, and well-versed with nature and all living beings. For a world where humans and nature live in harmony, I found this plot hole too glaring to not notice. The conversations between Dex and Mosscap also feel very elementary, and for beings who live in a really distant future, one did expect more.

“Sorry,” Dex said to the remains of the bug as they wiped it on a kitchen cloth. The robot noted this. “Did you just apologize to the bloodsuck for killing it?”

Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (p.37), Kindle Edition

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“It didn’t do anything wrong. It was acting in its nature.”

“Is this typical of people, to apologize to things you kill?”

“Yeah.”

“Hm!” the robot said with interest. It looked at the plate of vegetables. “Did you apologize to each of these plants individually as you harvested them, or in aggregate?”

“We … don’t apologize to plants.”

“Why not?”

Dex frowned, opened their mouth, then shook their head.

What I did like about the entire story was Dex’s ox-bike which is described as a vehicle of beauty and self-sustenance. It is used to travel, live in, can be made into a kitchen, opens up a bath, recycles water, and is powered by the sun. Solar punk as solar punk gets. I would love to see a designer visualise it. However, not much is written about the robot except that it is made from old materials and is fully waterproof. That is all. The final scene at the Hermitage is also lovely, where Chambers describes a beautiful, intricate building designed for the Gods, and now covered completely in foliage which is reminiscent of intentionally good architecture that humans undertake to carve their imprint in the sands of time. However, the fact that neither the monk nor the robot can start a wood fire in this hermitage without reading a book was, again, strange. Why the novel is called a ‘psalm’ for Mosscap is also not clear; maybe it is because the monk tries to explain human life to the robot, but there’s not much in the plot to suggest that Dex is a good storyteller of humanity.

The first book ends when Dex and Mosscap reach the hermitage, and the second book starts off on their return journey. In A Prayer for the Crown-Shy, Dex takes Mosscap on his tea-route through various landscapes in Panga — the Highway, the Woodlands, the Riverlands, Coastlands and the Shrublands — where Mosscap wants to meet humans and ask them the eternal question “What do you need?” This instalment explores Dex’s world and once again, Mosscap is the more interesting character in this novel. In each of the chapters, Mosscap is welcomed with great aplomb as humans have not seen a robot since the Transition and this is a first meeting or sighting of a robot since then. They live in these places, meet various characters (who all have white names somehow), and have a whale of a time eating, drinking, and helping the community.

The world building of these Panga landscapes is better than the first instalment, but still leaves room for imagination. Sibling Dex is non-binary and their family is polyamorous, but that’s where the diversity ends. A mistake we make as readers, while reading modern day literature, is that we expect stories to cater to our social and political affiliations, which is a grave mistake to make. So, I am very aware of this while reading utopian cozy punk. But then it begs me to question whether utopia looks like a uniform, un-messy, standardised society where human, internal dissatisfaction is the only conflict? I would argue that this is a question so large and so multi-faceted, the answer to it should not be over-simplified. Would it be possible to live in a world away from planet Earth where everyone looks like you, prays to the same Gods as you, and lives the same way as you? This is a question I will leave unattended here for all of us to ponder upon.

In the second book, Dex doesn’t know what is meant by the crown-shyness of trees and why this book is a prayer for them, I could only assume. For utopian fiction, Chambers’ Monk and Robot series offers a quick escape as modern literature is won’t to do, and I would have enjoyed it had I not been spending much of my time reading other material where humans are trying to imagine better worlds, better ways of living. If we are going to throw an image into the far walls of our future, I would love for these images to construct vivid, immensely green, multi-layered societies with motley characters. I want for us to explore the human condition more deeply without restraint, without over simplification, reckoning with the nags and gnaws of the human soul; and I want to follow it into uncharted territory while being scared and brave, over and over, and yet keep going.

Me and mine believe the further you distance yourself from the realities of what it means to be an animal in this world, the more you risk severing your connection to it. — Mosscap

Becky Chambers, A Prayer for the Crown-Shy, Kindle Edition

Bookhad

(11.10.2024)